Pits

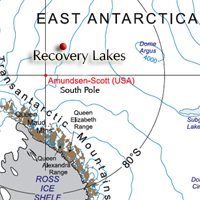

RECOVERY LAKES, ANTARCTICA– The last month has been a blur of flying snow from my shovel and endless white vistas seen from the windscreen of Jack, the finicky TL6 Berco I take turns driving. Even now, as Ole, our traverse doctor, drives Jack, I am typing in the back seat of the vehicle.

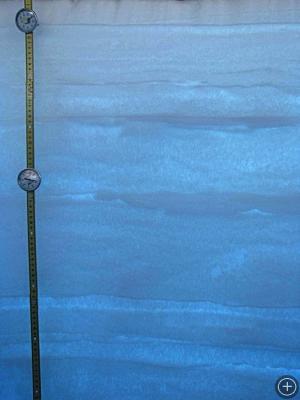

I am always on the move or shoveling, it seems. So far I have dug six 2 meter snow pits at various stops on the traverse. I dig the pits in order to get a close look at the surface snow and the layering caused by different weather and snow deposition events, and because these top 2 meters are fragile enough that the don’t always survive when shipped as cores back to the lab at home. The surface snow holds clues as to what is going on in the ice below. Some of the layering we see in surface pits is seen in deeper ice cores.

We can also get an idea of how much snow has fallen in a given area (thickness of the layers we see) and what processes (wind scours, snow fall) are going on at the surface. It’s a low-tech, labor-intensive way of getting a lot of information. Labor intensive because it involves digging a 2m deep by 1m wide by 2m long hole. I figure I’ve dug about 10 tons of snow so far, and made over 1000 different measurements of density, grain size, air permeability (ease of air flow in the snow), and thermal conductivity (ease of heat flow in the snow). These measurements give a physical basis for interpreting the climate record found in ice cores and the information that can be retrieved about the Antarctic plateau from radar and remote sensing signatures, which depend on, among other factors, grain size and density.

So I’ve been doing a lot of digging on this trip. It is good because if anyone needs to find me I’m either in one of my pits or in the science tent, a nice Weatherhaven tent constructed on the back of one of the sleds that is a mobile snow laboratory, complete with light table for looking at the layering in cores, and all my other equipment, including speakers for my iPod. I hate to admit it, but it’s a nice, more comfortable set-up than the cold room (basically a walk-in freezer converted into a laboratory) I work in back at home. Most days, it is -15 deg C (5 deg F) to -20 deg C (-4 deg F) in the tent, which is unheated to preserve the snow samples I work on, and out of the wind and pretty nice.

In addition to the work I’ve done in the snow pits, I’ve been able to help out with some of the other projects going on around camp. I usually help Tom Neumann with the hand coring we have to do. At each site, we collect what we call Beta cores, which will be cut up, melted, and tested for beta radioactivity. The peak in radioactivity signals the height of atomic bomb testing in the 1960s. This radioactivity was transported through the atmosphere here to East Antarctica in 1963-1964 as snow fall. In this way, we can date the layers in the snow, since we know that the layer with the highest radioactivity is from that year. A bit unsettling perhaps, but very, very useful.

I also helped Dr. Ted Scambos from the National Ice and Snow Data set up a string of temperature sensors we dropped down the last 90m hole we drilled. The temperature at different depths gives an indication of past temperatures, and can be used to determine if this area of Antarctica is getting warmer or colder—this is important since there are no direct measurements of temperature over time here (since there is no one here to make the measurements!)

It’s fun to help out with the other projects, as it gives you a different perspective on what everyone is working on. I also have been logging the boreholes that Lou is drilling with a borehole optical stratigraphy (BOS) system, which is essentially a camera used to record the reflectance of the layers in the hole. I have also been driving the vehicles when we are on the move, usually Jack, which is pulling a load of food and the living module where we eat. This is usually a bit boring as our top speed these days is around 10 km/hr (6.2 mph), which allows for Kirsty to make good measurements using her deep radar system. Faster than that and she does not have as good of a signal. Other times though, like when we are going through a white out, where at times you lose all perspective of what is up or down or where you are, or when the sastrugi are large enough that they cause the whole train you are pulling behind you to lurch sickeningly behind you in the rear view mirrors, it’s a bit stressful. We drive in 6 hour shifts, which gets tiring as well.

Jack is a bit difficult to drive. Kjetil, one of the mechanics who was at Camp Winter, where the vehicles were all fixed after last year’s problems, had explained to me that each vehicle is a bit different. The vehicles were all named after famous sled dogs, and the names seem to suit them, which is odd as well. I was skeptical until driving a couple different vehicles. I began by driving Chinook, which is relatively easy to drive. You want to drive in 5th gear, just speed up, put him in 5th, set the remote throttle knob on the dash so that you have about 1900 rpms, and down the ice cap you go.

Jack, on the other hand, is super touchy. It takes about 5-10 minutes of wrangling with the throttle knob to make him stay in 5th, sometimes even 4th. Moving the knob up or down even less than a millimeter sends him either bolting off at 13-15km/hr (way faster than we want to go), or zooming down through the lower gears if the rpms fall off. And then it takes even more finessing of the throttle knob to find Jack’s “sweet spot” where he’s keeping up with the others, but using as little gas a possible. This sweet spot of course is different from day to day as the surface conditions change, soft snow making it harder for him to pull his heavy load, and hard flat snow making him want to take off and pass everyone else. Even better, Jack changes speeds pretty drastically even with the remote throttle in the same position as the surface conditions change. As Svein says, “Jack is special.”

Svein has also encouraged me to try different things: monkeying with the throttle, driving in the tracks of vehicle in front of me, driving out of the tracks of the vehicles in front of me– which I guess makes the drive at least engaging if not relaxing at times. It’s a game to see which driver can get the lowest fuel consumption, as in, “I was getting 32 liters/hour, see if you can beat that.” Anything to make the time go by, I suppose. In a way, Jack reminds me of my dog at home, Baker. He’s stubborn, has a mind of his own, and is a bit crazy at times.

Besides driving and shoveling, the recreational activities I have managed are knitting (I knit Christmas ornaments for everyone on the traverse and yes, we had a tree—turkey, ham, gravy and stuffing too—we just celebrated on the 27th since that was a more convenient day for us) and skiing. A lot of the people on the traverse like to ski as recreation. It gives us some time to ourselves and away from camp where you can appreciate that you are in the middle of nowhere for a little bit, before scurrying back to the relative comforts of camp. I know that some have a goal of getting out to where they can’t see camp anymore, which no one has managed yet.

I had the full set of Arrested Development DVDs that I would watch at night in my bunk (not wanting to subject the rest of the group to American TV), but I’ve watched all the episodes now, and read the book I brought along, John Behrendt’s Innocents on the Ice, about his Antarctic traverse during the IGY in the 1960s.

It’s fun to think about the differences between our traverses. They definitely had a rougher set-up, while we ride in relative comfort. To be honest, we ride in relative comfort even in modern-day traverse standards, with a kitchen. They had a camping stove, shower (showers are pretty much unheard of in remote camps even today), a separate sleeping module (they slept in benches and sleeping bags in the vehicles) but got to see some fantastic, mountainous scenery, seeing some of the mountains for the first time. They were exploring totally unknown areas, with little warning if they were crossing crevassed areas unless they had a plane to do reconnaissance. We are covering places that haven’t been visited before, but have a pretty good idea of what we are getting into from satellite images, and have a great crevasse detector (Svein, our mountaineer, who operates a radar system that can detect them).

ZOE!! Amazing post! I love it…it puts me right there (except I’m sitting by a fireplace drinking whiskey). But seriously, thanks for sharing the experience with everyone. You guys are doing something really amazing right now and it is great that you can share it so effectively with us.

I just realized you are posting, so I get to look back at your older ones now. Keep ‘em coming! And watch out for those CREVASSES…