International Polar Years

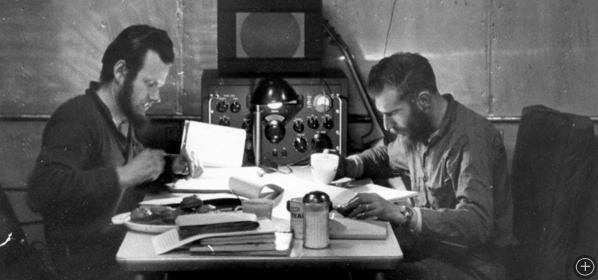

Radio engineer William MacPherson and electronics technician Cliff Dickey, two of eighteen men who spent the 1957 IGY winter at the South Pole.

IPY

This Ice Stories Web site was created in celebration of the International Polar Year (IPY) 2007–08, but what exactly is that? The IPY is a large international scientific initiative with a history that spans more than a century.

The inspiration for the first IPY, held in 1882–83, came from Austrian scientist, explorer, and naval officer Karl Weyprecht. He realized that studying the poles was an important way to understand meteorology and geophysics, but he also knew that it was a big undertaking; it couldn’t be done by one nation alone. Inspired by this idea, a group called the International Polar Commission was established in 1879; it organized the first IPY.

Twelve countries, including the United States, participated; they collectively completed fifteen polar expeditions: two to Antarctica, and thirteen to the Arctic. They probably spent more time trying to survive than they did doing science. There were also problems with countries publishing their own data rather than doing it cooperatively with other nations. But this first IPY was still very valuable. It set in motion the important idea of a collaborative, international scientific effort to study the poles, a spark that rekindled fifty years later.

The Dutch ship Varna got stuck in pack ice in January 1883 during the first IPY. Though the ice crushed the vessel, the scientists were able to continue their research by creating a makeshift observatory on the ice.

American Admiral Richard Byrd created an inland research station as part of the second IPY (1932-33). Photo copyright Ohio State University Archives.

The second IPY (1932–1933) was more scientifically successful than the first. It was proposed and promoted by the International Meteorological Organization as a way to study the newly discovered jet stream (a current of rapidly moving upper atmosphere winds) and its global effects. New inventions—airplanes and motorized sea and land vehicles—made life easier for the scientists. This time, the number of participating nations jumped to forty. Despite challenging economic issues (this IPY took place during the middle of the Great Depression), it brought advances in our understanding of magnetism, atmospheric science, and radio science and technology. Forty permanent observation stations were built in the Artic, and the second U.S.-backed Byrd expedition built the first inland research station in Antarctica.

The second IPY was followed, in 1957–58, by the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a major scientific event that propelled our scientific understanding, particularly of geophysics, far forward. It was proposed by prominent post–World War II physicists, who wanted to use some of the latest technology developed for the war—radar, computers, and rockets—for scientific research, particularly in the upper atmosphere. Sixty-seven countries and more than 4,000 research stations participated.

There were many breakthroughs. Important research into continental drift (when the continents change position in relation to each other) was done at this time. The Gambutserv Mountains, a huge completely ice-covered mountain range in East Antarctica, were discovered. Scientists were able to develop the first informed estimates of Antarctica’s ice mass by traversing the continent. The space age was born when the world’s first satellites (the Soviet Union’s Sputnik I in 1957 and the United States’ Explorer I in 1958) were launched. And the Van Allen radiation belts, which encircle the earth trapping cosmic radiation, were discovered. Twenty years later, in 1970, the scientific disciplines emphasized during IGY became the foundation of many of the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) programs and activities.

The twelve nations that were active during the 1957–58 IGY signed the Antarctic Treaty; their flags fly around the ceremonial pole at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station.

There was also a political outcome to the collaborative work of the IGY. The Antarctic Treaty, written in 1959 and ratified in 1961, states, among other things, that information has to be shared openly among researchers; that science done in Antarctic is for peaceful, noncommercial uses; and that no weapons development or testing can take place there. The Treaty also forbids mineral extraction of any kind and protects the terrestrial ecosystem of Antarctica, which makes it a much different place than the Arctic.

The current IPY is, technically, not a year, it’s two (March 2007–March 2009); the two years allow for two full field seasons at both poles. Like its predecessors, this IPY is also a major international, interdisciplinary scientific effort targeted at better understanding the polar regions. Thousands of scientists from over sixty countries, working on over two hundred research projects, are using state-of-the-art tools and techniques to conduct biological, physical, and social research. The goal of this IPY is to explore new frontiers in polar science, improve our understanding of the pivotal role of the polar regions in global processes, and educate the public about the Arctic and Antarctica (that’s where this Web site fits in). Its organizers also hope that this IPY will attract the next generation of scientists and engineers to the poles. The entire worldwide effort is overseen by the International Council for Science (ICSU), and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

It’s hard to know what breakthroughs will come from recent data collected, but this IPY has already taken a different kind of leap forward. During the 1957–58 IGY, the majority of countries, including the United States, didn’t allow women to work on The Ice. Now, women account for almost half of all IPY scientists, and many are project leaders. (To learn more about women and the Ice, click here.)