So how do we know where to dig?

One way is by digging “shovel test pits” (STPs), and that’s just what we did on Day 2 in the field.

The week before, the BASC logistics crew and several of our crew had gone on Friday to set up the two Weatherports (tents) that we use. The large white one is a combination storage/lunch area, and the smaller tan one is used as a bathroom facility.

When we arrived, lo and behold, the tan tent was collapsed and some distance from where it had been left. The door, the cover, and pieces of the metal frame were strewn everywhere.

It had been windy over the weekend, so at first we thought it had just blown down. Some of the crew secured the white tent with more tie-downs & gravel, and the rest of the crew dragged the pieces of the tent back and started to put it back up.

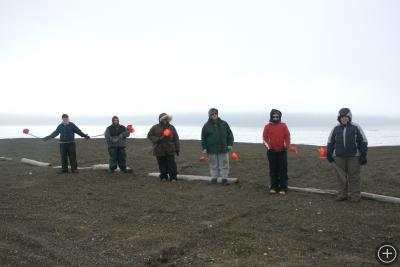

After that, we all took pinflags and started to walk the surface of the site, marking anything that had worked its way to the surface of the gravel over the winter. Since there were a lot of newbies, Laura & I, along with some of the more experienced grad students, had to check the flags, and wound up pulling some that were marking things we don’t collect.

In the end, we had a whole lot of pin flags showing things to be mapped in and collected.

The more we thought about the tent, the more we didn’t think it blew down. It had been tied to the surrounding logs with multiple ropes, and it was hard to imagine that all that had come untied just due to wind. Most folks here are really good at tying things down. The best guess is that maybe someone was having a bonfire somewhere on the point and was getting cold in the wind, and got the idea to borrow the tent. It looks like maybe they tried to move it as a whole and the frame collapsed. Anyway, we have it back up now.

]]>However, this does present a few training challenges. Archaeology isn’t something that is taught in North Slope Borough schools (or most other schools for that matter.) College-level or graduate-level field school students usually arrive with at least a theoretical idea of what archaeology is and how it is done. High school students don’t. That means we have to teach them enough so they can be effective in the field, but not bore them into quitting in the process.

We do short lectures about archaeological basics and how to fill out a bag, we practice filling out the various recording forms we use at the site, and introduce the theodolite (an instrument we use to measure horizontal and vertical angles.) We also spend parts of a couple days in the lab processing artifacts so students can get familiar with the sorts of things they will (or should) be finding, and get some hands-on experience on what will happen to the artifacts they will be collecting in the field.

We also try to do more active things. One is an exercise in mapping, ethnographic observation, and site interpretation. The more experienced students get to be the actors. Each pair of them gets a bunch of assorted candy and can do whatever they want for about 15 minutes. The newbies divide into groups, and each group watches one set of actors, recording what they do.

Next they rotate, and each group gets to map in what is left behind– the “material culture” if you will. This is pretty much equivalent to what archaeologists have to work with. Laura and I walk around asking leading questions like “So, do you notice any patterns? What could that be a result of?”

Then we get together, and the mappers (the archaeologists) get to describe what they saw, and what they think happened at the “site” based on what they saw. Then the people who watched the action (the ethnographers) say what they saw, and what they think it meant. After that, the actors get to say what they were really doing. And there is candy for everyone, lots of it.

It’s pretty interesting, can help students understand the limitations of both archaeology and ethnography, and also gets them thinking about what the things they see on a site might mean about past activity.

For a change of pace, we also go outside and practice excavating in the parking lot at my office. The newbies get to actually use trowels for the first time.

]]>The first to arrive were Brittany Osland and Shelia Oelrich, two volunteers who are good friends. They are originally from Soldotna, Alaska, although Britt is now based in Portland, Oregon. Neither of them are archaeologists, but they wanted to see Barrow, learn something about the people and the place, and try their hands at some archaeology. They came up on May 17th, and have been a huge help with the pre-season inventorying, organizing, and general straightening-up of field gear and the lab prior to the main season. They are old enough to drive the BASC truck assigned to the project, so can do supply purchases as well.

In addition, we currently have Paddy Colligan, who just finished an M.A. at Hunter College; Krysta Terry from Ontario, Canada, who just graduated from the University of Western Ontario and is planning to go on to graduate school; Dave Grant, who is working on a Masters at San Jose State in California (although he’s originally from Ontario too); Andrew Zipkin, who is an undergraduate at Cornell University; and Tony Krus, who just graduated from Hampshire College and will be going on to graduate school in the fall. On June 9th, Nadia Jackinsky-Horrell, a grad student at the University of Washington, will arrive to join us.

The BASC logistics staff took all the 4-wheelers (ATVs) out of winter storage and reassembled them. They have to take the windshields and shocks off to make them all fit into the limited indoor “warm” storage. Gear has been taken out, batteries have been charged, and software has been updated and loaded on to the ruggedized laptops for the season. The shovels, Pelican cases and so forth that we ordered are finally starting to arrive. Freight can be slow in the Arctic.

]]>Usually, they don’t tell you. You don’t get to see all the things that happen before the big discovery, the little baby steps that bring you to the point where the discovery actually can happen.

I think this is too bad. There’s a lot work and a lot of support that goes on behind the scenes, much of it done by people who are not actually scientists. So I thought I’d start out, before the crew shows up here in Barrow and we get out in the field, with a little behind-the-scenes look at some of the stuff that we’ve been doing to get ready for the summer field season, and some of the people who have been helping.

Some of our gear. Pictured here: 5-gallon buckets, dustpans, gloves, flagging tape, stakes, chaining pins in boxes, foil, water container, pelican case, and Action Packers to hold all of it.

Buying supplies

There are a lot of supplies an archaeologist needs in the field. Since most of these things can’t be bought in Barrow, and shipping can take a while, we started ordering them months ago. All of our field notes have to be taken on “Rite-in-the-Rain ™” paper, so they don’t get smudged or melt. We order reams of blank paper, and then laser printer our field forms onto them. Sharpies and mechanical pencils get used by the box, so we order ample supplies of those as well.

This year we bought a couple of new planning frames, which are squares that go over an excavation unit someone is mapping. They help people draw quickly and accurately. We also got several new north arrows for photography (for some reason they seem to grow legs and walk off) and a very nice new set of photo scales made by a company in France.

We also use a lot of Ziploc bags, in different sizes. We use freezer bags, both because they’re a bit more durable, and because they seem to work better in the cold temperatures we have up here. They can be bought locally, but in the quantities that we use, the store can easily be bought out. Therefore, we start buying them early in smaller batches. We’ve already got a huge stack in the lab.

Getting a crew

For the last several weeks, I have been reviewing resumes from graduate and undergraduate students who are interested in participating in the project. After posting project information on a couple of sites listing excavation opportunities, we got way more applicants than we could place. The result: a pretty rigorous winnowing-out process.

Since it’s a long (and expensive) trip up here and the field conditions are fairly harsh, it was really important to interview not only the applicants, but also their references, especially those who have been in the field with them. The decisions were finally made, and I had to do the tough job of notifying those who didn’t make it. I hope we’ve got a good crew. We’ll find out soon– the folks from out of town will start arriving on May 24.

We are now starting to get applications from local high school students will also be taking part in the project. We’ll be doing those interviews in the next couple of weeks, sandwiched around a trip to Yellowknife, Canada, to give a presentation at a meeting there.

The work before the fieldwork

At least two of the students from last year are back. One has already been working for a week in the lab. He has been cleaning and sharpening trowels, cleaning and restocking the boxes full of field equipment and supplies, and labeling the newly arrived equipment. He will be setting up some new shelving we just got and moving all the batteries and chargers onto that. It is time to start charging all of the radios, transit batteries, camera batteries, and computer batteries (not to mention the batteries for all the Ice Stories gear) that we take into the field with us every day.

]]>