Planning for an Arctic Season

BARROW, ALASKA– Each year, in the midst of the short Arctic growing season, Arctic researchers reflect on the season to come. We tell ourselves we will do things differently next year: remember this, remember that, or do something else in a different, more efficient manner. There are many logistics to consider.

It seems the first thing an Arctic researcher learns (and learns well) is how to pack everything but the kitchen sink. Sending off even for a simple forgotten or depleted supply item such as paper bags, bolts, etc., can take one to two weeks from the field. Then, there is the cost of multiple last-minute small shipments versus one large one ahead of time.

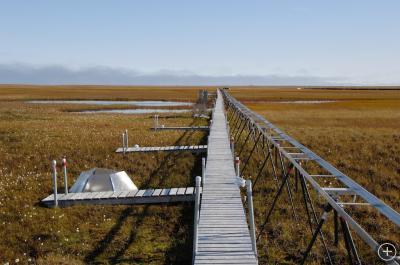

An eddy tower made up of expensive scientific equipment as well as pipe fittings, PVC pipes, and plastic tubing.

One notable international Arctic ecologist who did lots of research in other countries had a noteworthy piece of advice: “Never get ahead of your freight.” It can be rather embarrassing to get your whole team on site, only to have to wait a week or two until your equipment arrives.

When you do need something, last-minute express shipping is actually the least expensive way to go, given that it costs up to $200 per day per person to hire someone in the Arctic to wait ahead of time for your equipment to arrive.

To simulate warming on the tundra, we often use clear fiberglass panels that one might pickup at a garden shop.

I am not sure why, but it usually takes you at least one season in the Arctic to learn what your most critical resource really is: your fellow researchers, be they undergraduates, graduate students, technicians, or PI’s (project Principal Investigators.)

Indeed, selecting your field team can be the most important thing you do to ensure a successful season. When you share the bad mosquitoes, long days of freezing rain, muddy conditions, same old food, dirty clothes, lack of sleep, tight quarters, and no place to ‘get away’, camaraderie carries you that extra mile. One notable discovery I made is that the more closely the ratio of males to females on the team is one to one, the higher the spirits. (Another one of those mathematical puzzles…)

Paulo Olivas, a PhD student at Florida International University (originally from Costa Rica), about to head out into the field to install water wells. The water wells tell us where the water table is, and are nothing more than 1 inch diameter PVC pipes with lots of holes drilled into them. Paulo inserts them into the tundra then periodically goes back to see how far the water level is from the surface.

Here, Paulo uses sophisticated fiber optics to look at the sky and the plants. The instruments read the quality of light entering through both then, by comparing the plants to the sky, can determine the physiological state of the plants.

So, after Arctic researchers figure out their freight and learn the importance of the people they will work with all summer, how do they design experiments that work in Arctic conditions using equipment that: is not too heavy; is unlikely to break, freeze, or rust; doesn’t cost an arm and a leg; and is easy to make and repair?

Well, in some cases there is no alternative to an expensive piece of equipment– be it a data logger, data analyzer, radiation sensor, etc. However, invariably, prior to each season, I find myself walking the aisles of hardware stores, trying to come up with new and novel ways to implement new experiments using readily available materials. In part, this can save money, but more importantly, hardware stores are typically more accessible in the Arctic than scientific warehouses!

Using a car washing wand, Paulo holds his light sensor over this experimental plot to measure the plot’s activity. Note that the plot is bordered with a white PVC pipe– the kind you might purchase at Home Depot.

Handling these logistics are just some of the things that scientists do during the off-season while they plan for the next session in the field. This is, of course, on top of analyzing the data, writing reports, attending meetings, publishing papers, writing the next proposals, teaching, and interacting with the public.

No comments

No comments