Bay of Sails

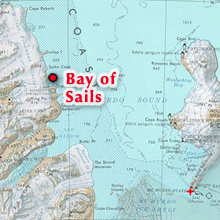

BAY OF SAILS, ANTARCTICA– One of the main goals of SCINI is to explore new areas. Our first target this year is Bay of Sails. I selected this general location because it is an “iceberg graveyard” – a place where icebergs collect due to winds and bathymetry. Located across McMurdo Sound on the Antarctic continent, it will be an ideal comparison site to Cape Evans on the Ross Island side of the sound, where we looked at iceberg impacts last year.

Icebergs are moved by wind and currents, and when they come in contact with the seafloor, plough across it leaving a swath of destruction. Cape Evans, on the eastern side of McMurdo Sound, is bathed by plankton-rich water from the open Ross Sea, providing a good food resource to benthic communities during the summer months. But at Bay of Sails, on the western side of the sound, the water has spent a long time circulating in darkness under the thick ice of the permanent Ross Ice Shelf, so it is very oligotrophic, or food-poor. I am interested in the differences between how these two communities recover from iceberg disturbances.

To start this effort, we did a reconnaissance helicopter flight. Scottie, our pilot for the day, flew us in beautiful loops and spirals over the dozen icebergs scattered in the bay. We were looking for a berg that was grounded on the seafloor, was in about 50 m water depth, and was close enough to other icebergs that we had alternate target options. Since the bathymetry in this area is poorly known, I had to guess at depths based on distance from shore and iceberg height. I selected a moderate-size, tabular-looking berg about 2 km from shore. It was a good choice, but a better one was about a km further offshore, as we discovered from our initial survey with an extremely high tech weight on a tape measure.

Parallel with selecting the camp location, we have been packing up camp gear. 335 pounds of food, 330 pounds of water, sleeping bags good to minus 40, tents, fuel for the stove and heaters, sleds, safety supplies, another 1485 pounds of stuff. And then there is the science equipment – drills, electronic gear, the ROV itself, power supplies, batteries and generators, all in all 760 pounds of toys. Then there is the 1000 pounds of people. Not to say we are fat, but several of us are up to three desserts per night. Yow!

All of this is sorted into classifications of Can Freeze, Do Not Freeze, and Keep Frozen (some of the food). Bags and boxes are weighed and tagged. Hazardous material is certified as safe to fly. Much of the Can Freeze camp gear has gone already in an overland (well, over-sea-ice) traverse to a fueling depot about 10 km from Bay of Sails. The helicopters will carry it the rest of the way to us.

It’s a little nerve-wracking, making sure we remember everything, and enough of it. I have lists, and lists of lists, and I wake up in the middle of the night to make more lists. Remembering to bring all the things we needed to Antarctica was bad enough, but the field camp list must be pared to a minimum yet not leave out anything. We will get a resupply flight after a week, to bring us more water, so we do have that opportunity to fix any bads, but it would be very unproductive, not to say embarrassing, to have forgotten the batteries to the joystick to drive the ROV.

Team SCINI at field camp I: Kamille, Dustin, Isabelle, Francois, Stacy and Bob. Doh, Dustin has forgotten his black Antarctic uniform pants!

Tonight as the sun dips to touch the horizon I think that we have all we need to survive. But I am worried about the engineers getting their stuff packed; they are still out doing tests at 10 pm, 12 hours from when it must be on the helo pad. I am beginning to think that procrastination and engineering must go hand in hand. I think a walk up Ob Hill is in order to reduce my stress!

Thanks for the information Stacy, We will also ask the PolarTREC site, but what is the longest you have been or can stay at a field camp? Just by your descriptions we see that it is quite an undertaking to have all that you need for the remote research. We have one more question…please. Will you be publishing your data from SCINI on line??? so that we can see the culmination?

Have fun, we are loving all the blogs and updates!

Jose, Parker, Misty, Zauria, Beto, Adrian, Lane, Marvin and Jillian!

Wow you have a full crew and so much work that you are doing plus all of your lists.Hope all continues to go well and thanks for the pictures too.

Hi Jose, Parker, Misty, Zauria, Beto, Adrian, Lane, Marvin and Jillian!

Some people stay in field camps for months. But field camps come in many different shapes and sizes. Some are large and have nearly permanent buildings, are staffed with a cook and manager, and support dozens of researchers. Some are small, only a few scientists in one or two tents. Two weeks is about as long as I would want to spend in a small camp, as it is very hard work and after 2 weeks of it I am pretty exhausted. In a larger camp, a month or more is very comfortable.

All the data from SCINI will be available online, but it will be a year or so before I can find a site to host it permanently and get it all uploaded and quality checked. We will also be writing papers about the work we have done; Francois is working on the first paper now. If there is specific data that anyone wants, I am happy to provide it to them any time!

Your questions are fantastic, please keep asking!

Best, Stacy

Hello Stacy!

My students and I are really enjoying reading your posts and hope that you have remembered everything you need while at field camp. Unlike here in Florida, you can’t hop in a car for a dash to the store if something is forgotten. And, our forgetfulness is not a possible matter of life and death!

The students have a few more questions for you…

1. Grecia: How do the computers function at such low temperatures? Does the cold affect the battery life, and computer components?

2. Megan: What is your greatest concern when under the ice?

3. Michelle: When you go diving, are you the only one under the ice or do you have someone with you?

4. Chase: What are you thinking about and feeling when under the ice doing research? Do you get distracted by what you see?

5. Marcel: How deep have you dove when under the ice and how long do you usually stay submerged?

6. James: What kinds of sea life do you most encounter in this very cold water?

We hope to hear from you soon. Keep safe!

Mrs. Hutchins’s 6th graders at Suwannee Middle School

Hi Mrs. Hutchins and 6th graders,

You should see the lists I have, and lists of lists, to be sure that nothing (well almost nothing) gets forgotten. But another help is creativity – if we forget something, we can usually make a suitable substitute from parts or by repurposing other things we have. it is amazing what you will come up with when you need to!

Grecia – We try to keep our computers at temperatures that are not too low, to help keep them running well. You are right that batteries do not do very well at low temperatures – we run our computers off a generator and uninterruptable power supply, so we are not entirely dependent on batteries. But we have more trouble with the screens, which lose contrast at low temperatures, and may even be permanently damaged. And we have the most trouble with power cords, which are not designed for such low temperatures, and often have plastic or rubbery coatings that are very brittle in the cold and break. Fortunately the wires inside are less likely to break, and we can repair the outer coatings.

Megan – When I am diving under the ice I worry most about not being able to find the hole back to the surface. So I am very careful to keep an eye on it and always know where I am relative to it.

Michelle – When I am diving I always have a buddy with me. Sometimes there are other buddy teams in the water at the same time. And sometimes SCINI is in the water too!

Chase – I get very distracted by the beauty of the world under the ice. And I am usually thinking about many things – the tasks I need to do on the dive, where the dive hole is, where my buddy is, how much air I have left, and how deep I am, as well as how lucky I am to be doing something that I love so much in such an incredible place. I feel very honored to be able to experience Antarctica underwater, it is a truly special part of our world.

Marcel – The deepest we can dive is 40 m, or 130 ft. But SCINI can go to 300 m, or 1000 ft! I usually stay underwater for about 45 minutes. SCINI missions are usually 4 hours long – and if the pilot, navigator or engineer get tired, they can switch out with other people to take a break.

James – We are now studying an area called Knob Point. The two kinds of sea life that are most abundant there are sponges, and bryozoans. And there are a LOT of them, because there is a lot of light, and thus a lot of food available here. At Becker Point, where there was very little light and food, the two dominant animals were anemones and brittle stars.

I hope you are all staying warm in beautiful Florida! Thank you for your questions!

Best, Stacy

Stacy,

We have been studying using GPS technology to determine absolute location. We also have made an Antarctic “geocache” which has information about Antarctica. We’ve hidden it in the community and published the coordinates at http://www.geocaching.com. We are going to check out GPS units to go find it and other geocaches.

Do you know that there are geocaches at McMurdo Station and nearby? Do you go geocaching? What is the absolute location of the station plus the coordinates of your field camp? We would like to place a marker on our GoogleEarth maps.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Mrs. Hutchins 6th grade students

Hi Mrs. Hutchins 6th grade students!

I have never been geocaching but it looks like fun, and I know that some folks down here do it. The location of our lab at McMurdo Station is 77 degrees 50.85 minutes South, 166 degrees 40.023 minutes East. Our Bay of Sails camp was at 77 degrees 19.92 minutes South, 163 degrees 38.19 minutes East, and our Becker Point camp was at 78 degrees 08.60 minutes South, 164 degrees 10.88 minutes East.

You may be interested that to navigate SCINI we set up an “underwater GPS.” GPS signals do not travel through the water, so we put transducers in the water that send sound signals (that will travel through water) and are connected in air to radio tranceivers that send information back to the main computer that is running SCINI. The ROV has a pinger on it, and each of the two to five transducers record the exact time that it receives the ping. Then the computer plots the circle of distance from each transducer based on the speed of sound in seawater. Can you figure out why when we have only two transducers, we have two possible locations, but that as soon as we have three or more, we know exactly where we are?

Great questions and have fun with the geocaching!

Best, Stacy