A Tale of Two Cities

ROSS ISLAND, ANTARCTICA– In this land (Antarctica) and an ocean far away (to most of you), but not long ago (in the past weeks or so), a scenario was played out that in days long past may once have happened, in fact, near by to where you are, but involving penguin cousins.

Of what I speak is a seabird colony existing where the marine ecosystem has not been subject to wide-scale pollution from agricultural and civic runoff, fish depletion, introductions of alien species, harmful plankton blooms (“red tides”) and lots of other things that currently ravage most marine ecosystems of the “civilized” world. I speak of the Ross Sea, the last ocean on Earth where seabirds are capable of being too successful in their breeding. Hmmmm, yes, you heard me right. That is a statement that should give you pause for contemplation, and refers to a concept foreign to most marine ecologists. And what could I possibly mean by this? How can a colony of seabirds ever be too successful?

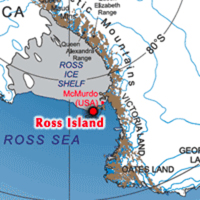

If you’ve been following my previous dispatches to Ice Stories for this recent Antarctic summer, one was called “Royds Tranquility” and another was “Beaufort Chaos”. In those I reported on the contrast between the Royds penguin colony (one “city” in this story, 2000 penguin pairs) and the more populous colony at Beaufort Island, the other city (60,000 pairs). The Royds colony was very quiet but at the time miserably failing owing to the 70 km walks that most parents were making to find the ocean and food…and 70 km back. The extent of fast ice was very unusual owing to very calm winds last winter and spring. Other than birds attempting to remain resolute on their nests, no others were present. Deserted eggs were everywhere, as more and more adult penguins giving up and going off to feed, their mates choosing not to return.

At Beaufort Island, where the ocean was at the penguins’ doorstep, just a short skip away, penguins were coming and going in multitudes, and because many nested in suboptimal habitat– being forced to do so because the good spaces had all been taken– some were losing their eggs too. But there were huge numbers of eggs still under other parents, being warmly incubated. In addition, due to a short journey from wintering areas just before nesting, all colonies, Royds included, began the season with their respective breeding populations at maximum, i.e. above normal. “Everybody”, it seems, attempted to nest! [If you’ve not read the earlier dispatches, perhaps do so before proceeding further in this one.]

About 40 km to the east of Beaufort, the colony at Cape Crozier was in a similar state to Beaufort: maximum proportion of a large colony, twice the size of even Beaufort (150,000 pairs), attempting to breed. Well, we could not follow up at Beaufort (couldn’t get there at the end of the season) but did have the opportunity in regard to Crozier. I think the stories for both Beaufort and Crozier were pretty much the same, although, being smaller, likely Beaufort didn’t have quite the problem experienced at Crozier.

At all our penguin colonies, there are the “super breeders” who almost always produce young– despite conditions– and then there are the “other” penguins. Mainly the super breeders have learned, through experience, about the vagaries of factors that penguins need to know about. This involves just 25% of the population, or thereabouts; the remainder of penguins almost always fail unless conditions are really easy. This season, the super breeders came front and center at Royds. Not only did they successfully hatch their eggs (unlike the klutzes) but also raised the maximum of two chicks. Therefore, even though 75% of nests failed, the total average chick production of the colony was 0.6 chicks per nest, which isn’t all that bad, given that in good years, an average 0.9 chicks are produced among all nests in which eggs are laid.

What these super breeders had figured out was that they could feed through narrow cracks in the ice and not walk all the way to the open ocean. Then, the ice opened into a polynya [patch of open water in the ice] off Royds, as I described in the “Minke Friends” dispatch. From then on, foraging was easy and the Royds chicks ballooned to become heavier than even last season, averaging around 3800 grams by the time they were 6-7 weeks old and within a week or so of fledging. That’s BIG for an Adélie penguin chick! As is the usual, the Royds chicks didn’t form crèches [groups of penguin chicks] because almost all the time, at least one parent was present to protect them.

Below are two images of Royds, taken on 17 January 2009, showing all the adults present. The reason that there are an equal number or more chicks than adults is because most chicks had a sibling…so two chicks for every successful nest.

So now, what about the other penguin city, the one at Crozier (standing in for Beaufort in this tale)? At Crozier, not only did a maximum number of birds attempt to breed, but almost all successfully hatched their eggs. This was because initially finding food was easy, as long as a parent only had its own mouth to feed. Not long after peak hatching, though, the parents began to make longer and longer foraging trips as they depleted food nearby. Of course these seabirds had help from whales and fish in this consumption, unlike the case for any other place in the World Ocean.

Chicks at first did ok, but once they reached the age of maximum growth rate, around 3 weeks of age, troubles began for Crozier. Eventually, parents’ trips reached three days long and less food was returned as some was digested on the trip back (these penguins hold the food in their stomachs, and then regurgitate it to their chicks — see previous dispatch — and once that cold wad begins to heat up in the parents’ stomach, it begins to digest, a common occurrence when the trip back to the colony is more than a day long). Well, basically the chicks at Crozier, though reaching appropriate size (height) for their age, became way under weight. At week 7 they were more than 1 kilogram (1000 g) lighter than Royds birds, and their feather development was halted. In fact, average weight was lower than we’d ever measured it at Crozier. Many chicks began to die of starvation. There were just way too many of them to be fed with the result that almost all were under-fed. In fact, breeding “success” at Crozier was 1.0 chicks crèched per original nest (it’s usually no better than 0.9). Wow! That’s a lot of chicks when you consider there were 150,000 nests to begin with.

Looking to the immediate future, it would seem that the chances for eventual survival of the Crozier chicks is close to zero, quite in contrast to the fat, vigorous but many fewer chicks at Royds. The Royds chicks should have a great chance for survival.

Below are images from Cape Crozier taken on 20 January. The contrast with Royds is dramatic, as almost no adults are present, even though the chicks are just a few days older than those shown in the images above from Royds. Sad.

Here you can see lots of chick carcasses. These chicks, unfortunately, have died of starvation. Also sad.

So, this is all pretty amazing, but we had to go through the entire season to see how things played out, and flip-flopped Royds vs Crozier. In the last several seasons (2001-2005), we witnessed somewhat similar events at Crozier, but chalked it up to effects of the big icebergs that were present then. The icebergs occupied a large portion of the Crozier colony’s foraging area.

Those icebergs have been gone now for two seasons. So, we have to consider other ideas to explain what is going on now. Perhaps, it seems, Cape Crozier has grown too large!! This rarely could happen to a seabird colony elsewhere in the world. Mostly this is so, because the population is kept low by pollution, toxic die-offs, invasions of feral animals or other type events; or breeding success is low owing to difficulty in finding food early in the season (over-fishing). In some warmer-water colonies of seabirds, where the environment allows the population to be present year round, a portion of large populations may just hang out in waters nearby and not participate in breeding. That doesn’t seem to be an option for migratory seabirds nor for seabirds that live in extreme environments, in both cases like is the case for Adélie penguins.

Well, ok, it was a very “educational” season for us, as are many. To complete our education, though, we have to be present in 4-5 seasons hence to tally the winners and losers among the penguin cities. That’s because young Adélie penguins spend their first years at sea and don’t visit the colonies.

For this season we are done, and here is what our camp at Cape Royds now will look like through the winter darkness. (See dispatch, “So, You Want to Be a Penguin Researcher?” for a view of the camp all set up.) In a couple of months you’ll need a flashlight to see this, our camp in a small box….well, a slightly large one.

Great to get timely status report on the penguins.

Is there anything that can be done to assist the Cape crozier colony?