The Iñupiaq People of Barrow, Alaska

The Iñupiaq, which translates into the “real people,” have been in Barrow, Alaska, for about 4,000 years. To survive in the harsh Arctic environment, the Iñupiaq developed a deep understanding of the area’s natural resources and how to make good use of them, and created a culture of cooperation and sharing. They traded with their neighbors (and with others in the 1800s), and hunted, primarily seals, caribou, and bowhead whales.

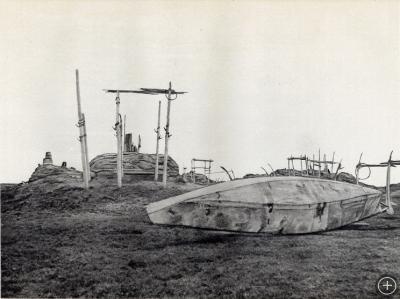

Bowhead whale hunting was, and continues to be, important to the Iñupiaq culture—not just for the food it provides, but for the sense of community and cooperation it creates. The whales can weigh as much as 60 tons, which means they have to be hunted by groups of people working together with a whaling captain. When they kill a whale, the Iñupiaq thank it for giving its life to them, and the whole community shares in its bounty. Much of the equipment traditionally used by their ancestors, including a umiaq, or sealskin canoe, is still used today.

Contact with Europeans came in 1826, when two British men arrived and renamed the area Barrow (the Iñupiaq named it Ukpiagvik, “the place for hunting snowy owls”). By 1854, the first commercial whaling ships arrived at Barrow and trade began between the Iñupiat and European whalers. From 1852 to 1854 the British overwintered twice looking for a lost expedition. Shortly afterwards, the first commercial whaling ships arrived at Barrow and trade began between the Iñupiaq and whalers from the East Coast of the United States.

Trade and contact with the outside world changed the Iñupiaq way of life. They acquired new technology, including guns, which they incorporated into their traditional hunting methods. Missionaries arrived in the late 1800s, introducing western religion. Contact also exposed the Iñupiaq people to new diseases. As a result, the population declined until western medicine was introduced in the 1920s.

In the last fifty to one hundred years, the people of Barrow have seen rapid change. The North Slope is home to the largest oil reserve in the Arctic. The oil and gas industry has brought many new jobs to the area. Barrow is also part of the North Slope Borough, a large incorporated area established in 1972, which has also added government and private jobs as well as modern conveniences. Now, light is supplied by electricity instead of seal oil, for example, and dogsleds have been replaced by snowmobiles.

Today, 60 percent of the people in Barrow are Iñupiaq; 98 percent of the people in the other seven North Slope villages are also Iñupiaq. While much has changed, many traditions remain. The Iñupiaq continue to do subsistence whaling and other hunting, for cultural as well as practical reasons (food is very expensive there and hunted food is much healthier than store-bought). Many Iñupiats work part time to accommodate their subsistence way of life, and some jobs are structured so they can take “subsistence leave.” With climate change looming, however, the Iñupiaq people are now in danger of losing their major food sources as well as some of their traditional ways of life.