Aurora

There is at least some compensation for enduring the harsh climate at extreme northern and southern latitudes: the chance to see an aurora. Known as aurora borealis in the north and aurora australis in the south, auroras are natural light displays caused by electrically charged particles colliding with the atoms of gas that make up our atmosphere.

It all begins in the sun, where extreme heat rips atoms apart to form plasma, a gas made up of electrically charged particles. These charged particles stream outward from the sun in what’s called the solar wind.

Like a protective bubble, the earth’s magnetic field, or magnetosphere, deflects most of these particles away from earth. But some charged particles do enter the magnetosphere and get funneled towards the earth’s north and south poles. When these charged particles collide with the gases in our atmosphere (mainly nitrogen and oxygen) the energy of the collision causes the gases to glow, a lot like the glowing gas in a neon sign.

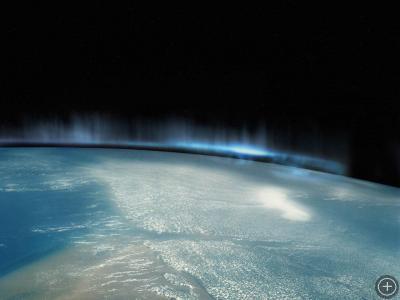

As variable as they are beautiful, auroras can appear as ribbons, bands, arcs, or curtains—sometimes still, sometimes seeming to dance or pulsate. Green and red auroras are most common, but they can also appear in shades of pink, blue, or purple.

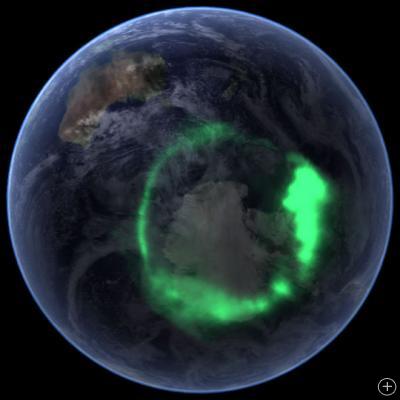

Since charged particles enter our atmosphere at the poles, auroras are most often seen at extreme latitudes. In the north, a common latitude for sightings is 67°, or roughly the latitude of Fairbanks, Alaska. During geomagnetic storms, however, auroras can be viewed at much lower latitudes. After a major solar event in April 2000, the “northern” lights were visible as far south as Florida.

Aurora Australis as captured by NASA’s IMAGE satellite, overlaid onto NASA’s satellite-based Blue Marble image.

Auroras are naturally unpredictable, but the likelihood of their appearance can be predicted, thanks to a satellite called the Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite, or POES, which measures the particles entering the upper atmosphere. Data from this satellite are compared to statistical data of auroral sightings to produce a prediction of where auroras are currently most likely.