Floating Across Alaska to Study Vegetation Change

In the last few years, public attention has focused on the melting Arctic sea ice, a dramatic response to global warming. But changes of a similar magnitude are happening across the Arctic landscape. The primary change underway throughout many regions is a shift from a shrub-free to a shrub-dominated tundra.

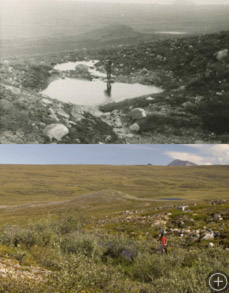

Chandler River, North Slope, Alaska. The top photo (black and white) was taken in 1947 by a Navy photographer; the bottom photo (color) was taken in 2001 by Ken Tape. Comparing these photos allows scientists to see the landscape’s change over time.

This change has been documented on a multitude of spatial scales — in feet (or meters) at the Long Term Ecological Research site at Toolik Field Station, for example, and in satellite images of the entire Arctic region.

Understanding these landscape changes is important because vegetation influences the exchange of carbon dioxide between the earth and the atmosphere. Higher concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are likely responsible for higher global temperatures. Changes in vegetation also affect animals such as ptarmigan (game birds), musk oxen, moose, and caribou that live in the tundra ecosystem.

To understand some of the details of how global warming is affecting Arctic tundra, Ken Tape, a graduate student at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and his colleagues floated down two rivers in Alaska to sample numerous locations where repeated old photos show that shrubs are expanding, and compared those locations to ones where the vegetation is not changing.

Another example of “repeat photography.” The top photo was taken in 1957 by George Kunkel. The bottom photo, taken in 2007 by Ken Tape, shows how shrubs have thrived in the last half-century, coincident with climate warming.

Combined with data about soil temperature, soil moisture, soil carbon content, species presence and abundance, and permafrost depth, Ken’s photographic data will help create the baseline measurements that will allow the next generation of scientists to document and map future landscape changes.

Ken’s work is part of the National Park Service Arctic Network Long-Term Monitoring Program, a collaboration fostered by EPSCoR Alaska.